Most apps collect some information about the user. Sometimes, they really need such data to operate: For example, a navigation app requires your positioning information to build a convenient route for you. Developers often use information about you to monetize or improve their service — with your prior consent. For example, they may collect anonymous statistics to find bottlenecks in their app and understand along what avenue it needs to be developed.

But some developers may abuse your trust by stealthily collecting information unrelated to their app’s functionality and by selling your data to third parties. Fortunately, you can use a couple of services to bring such apps into the open.

AppCensus

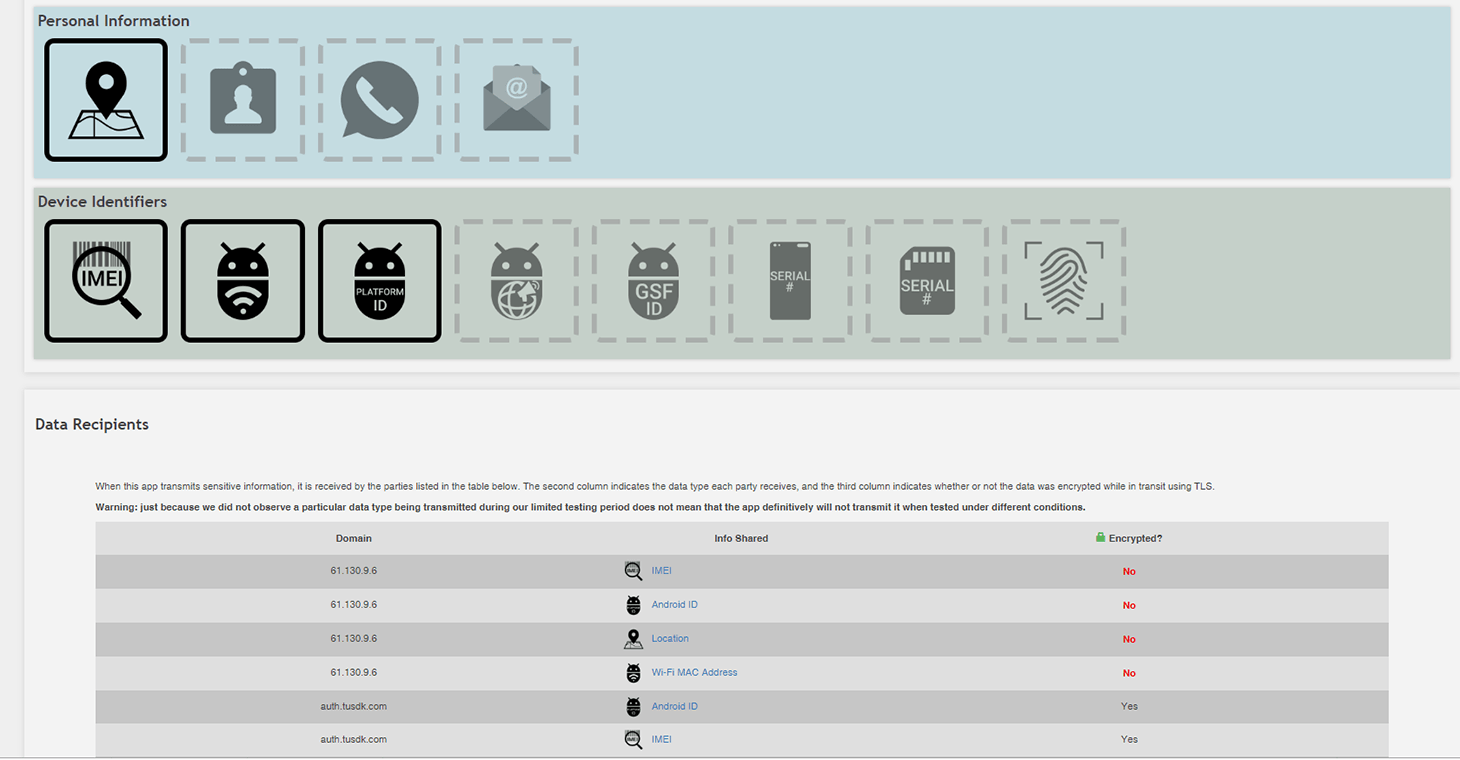

The AppCensus service helps you find out what personal data apps collect and where they send it. It relies on the dynamic analysis method: The app is installed on a real mobile device, granted all the required permissions, and actively used for a certain period of time. All the while, the service keeps an eye on the app to see what data it sends, and to whom, and whether the data is encrypted.

This offers an insight into the app’s real world behavior. If you feel uneasy about the information AppCensus digs up, you can avoid using the app in question and look for an alternative that keeps its nose out of your unrelated business. But the information AppCensus has collected may turn out to be incomplete; each app is tested for a limited time, and some app features may take a while to get activated. As well, AppCensus analyzes only Android apps — and only those that are free and public.

Exodus Privacy

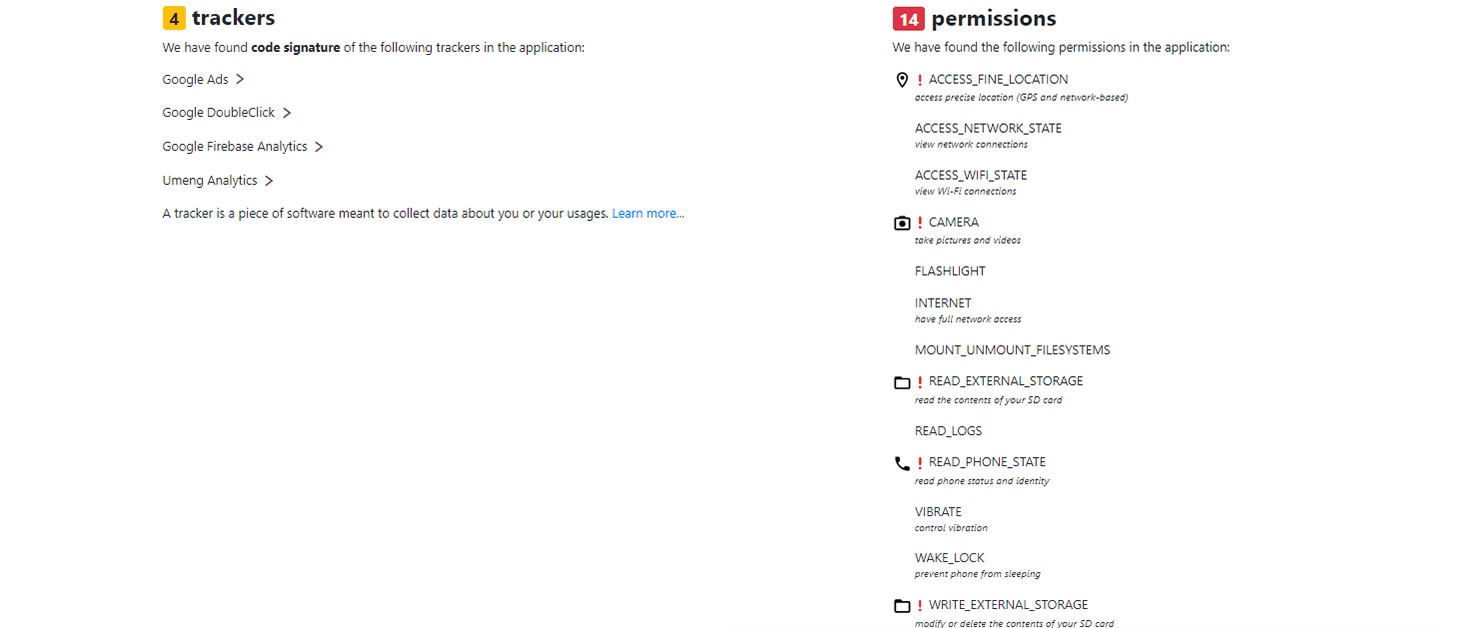

Unlike AppCensus, Exodus Privacy studies apps themselves, not their behavior. The service analyzes the permissions an app requests, and it looks for built-in trackers — third-party modules made to collect information about you and your actions. Developers often equip their apps with trackers provided by advertising networks, which are made to learn as much as possible about you for the purpose of delivering personalized ads. At present, Exodus Privacy recognizes more than 200 types of such trackers.

Speaking of permissions, Exodus Privacy analyzes them from the viewpoint of the danger they pose for you and your data. If an app should request permissions likely to compromise privacy or disturb the device’s protections, the service will mention it to the user. If you believe an app does not need some potentially dangerous permissions, it is best not to grant them. You can give it more rights at a later time, if you choose to.

Apps’ little secrets

Both services are very easy to use. A simple search on the app’s name will yield thorough information about what data it collects and where the data goes. Unlike AppCensus, Exodus allows users not only to pick apps from a list, but also, using the New analysis tab, to add apps from Google Play for analysis.

To provide an example, we looked at a selfie camera app with 5 million downloads from Google Play. Exodus Privacy shows that the app uses four ad trackers and demands not just access to your camera, but also your device location, which is not strictly necessary for it to operate (in theory, device location may be used for a good purpose — to add geotags to EXIFs of the pictures it takes), as well as your phone and call data, which is anything but necessary for this kind of app.

The same app analysis by AppCensus only adds more concerns: According to the service, the selfie camera doesn’t just get access to your phone or tablet location, but it also sends this information, along with the IMEI (your device’s unique cellular network identifier), MAC address (another unique code that can be used to identify your device on the Internet or local networks), and Android ID (a code assigned to your system when you first set it up), to a Chinese IP address — all without encrypting it. Forget about good intentions, there’s no good reason for all that.

The data that can be used to unmistakably follow your gadget’s movements is fed to someone in China, and can also be intercepted by anyone while in transit. Who this data is sold or passed to is a good question to ask, too. Yet in their privacy policy the developers claim they collect no personal data about the user, and do not pass device location information to anybody.

Is there any protection against spying?

As you see, a popular app with an unremarkable privacy policy can compromise your sensitive data. Therefore, we recommend that you treat mobile apps with caution:

- Do not just install them for no reason. They can spy on you, even if you never use or open them. If you no longer need an app that is already installed, delete it.

- Use AppCensus and Exodus Privacy to scan unfamiliar apps prior to installation. If the result disconcerts you, look for another app.

- Do not necessarily grant apps all of the permissions they ask for. If unclear about why the app would need this or that information, deny access to it. Check out this post for more about permissions in Android; also, you can easily control apps and permissions using Kaspersky Premium.

privacy

privacy

Tips

Tips