So, you want to buy NFTs.

You’ve read the stories about people getting immensely rich with them or cryptocurrency, and think — why not me? Well, “You thought wrong” was a working title for this article, but it’ll be a long while before we reach this conclusion. The NFT ecosystem is fairly complex in itself, and the technologies it involves are built on top of others. And understanding what NFTs are, unfortunately, requires establishing some base knowledge.

For this reason, this article is divided into three parts, ordered by increasing level of abstraction. In the first part, we’ll talk about blockchain and the general ideas behind cryptocurrency. This will allow us to dive into the NFT ecosystem in the second part, before finally studying the societal and political impacts of this industry.

Blockchain technology

While blockchains can hardly be considered “new technology” in 2022, I’m always surprised to discover how limited most people’s understanding of them is. If you already know what blockchain is, feel free to skip this section. If you don’t know, while you were really considering getting rich off of cryptocurrencies, this should probably be your first red flag — were you really hoping to earn money from entities whose core concept totally eludes you? For the sake of brevity and clarity, the following introduction will involve a number of oversimplifications, but hopefully it will be good enough to understand the one aspect that I’ll keep coming back to: what problem blockchains were created to solve in the first place.

Blockchains are “distributed ledgers”. In other words, they’re a way of storing data in a distributed fashion. On paper, this doesn’t seem groundbreaking at all: the IT world has been using distributed databases for a long time to allow companies to replicate and synchronize data across multiple locations. But these locations are usually controlled by a single, trusted entity (that is, a company).

Blockchains have an additional property: they can be distributed among many entities that don’t necessarily trust each other. To illustrate why this is needed, consider Bitcoin — the cryptocurrency that was the first successful application of blockchain technology. Bitcoin was designed as a monetary system that wouldn’t need any central authority to operate. It’s a distributed database that contains information about who owns how much, and this database gets updated every time transactions take place.

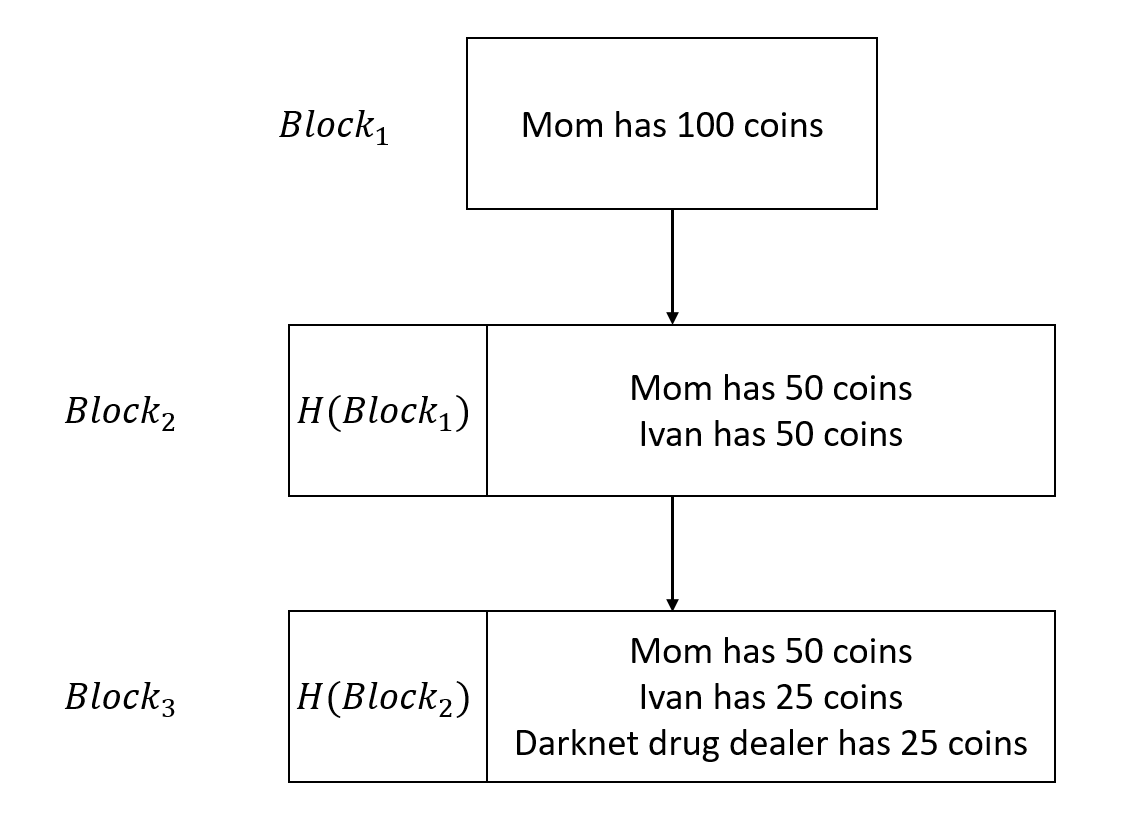

In my experience, the “distributed data storage” aspect of blockchains is usually well understood. Most people have a good grasp of the idea of blocks of information chained together, containing a checksum (or cryptographic hash, called H in the example below) to attest the integrity of the previous link.

Since all the participants of the network need to have a consistent copy of the blockchain, there are a number of security challenges to address. What prevents you from updating this distributed database with a record that says you now own 10,000BTC? After all, since there’s no central authority, your word is as good as that of any other network participant. Or, an even better idea: is there a way you could spend your money twice by sending multiple transaction orders before the information has had time to spread across all copies of the ledger?

The technical answers to these problems matter less than their consequence: blockchains are as much a means of distributed storage as they are consensus-building algorithms. I want to reiterate this point, because it’s so crucial to understanding blockchains: what they actually bring to the table is their ability to consistently share information between multiple untrusted parties who have a direct financial incentive to poison it with false data.

Cryptocurrencies (are not currencies)

So here we are, armed with a nice data-sharing tool. Finding applications for it, as we’ll see, turns out to be a much more difficult task than you might think. In 2009, an unknown individual (or group of individuals) using the moniker Satoshi Nakamoto released the first public version of the Bitcoin client, following a whitepaper a year before. The idea behind Bitcoin was to create a purely digital, peer-to-peer currency system that would be able to function without banks — central or otherwise — and without the support of any state. In the context of Bitcoin, the ledger acts as a record of all existing “coins” in the system, where each block represents a number of transactions. The bitcoins move around “wallets” (the rough equivalent of a bank account); users can prove ownership of their wallets using public-key cryptography, and this gives them the right to send their money to others.

On paper, the idea sounds solid. But does it work? While there are many facets involved in answering this question, we may simply begin by looking at today’s practical uses of Bitcoin, which, to-date remains the foremost crypto-asset. The first recorded purchase of physical goods with cryptocurrency (a pizza for 10,000 BTC in 2010) was perceived as an encouraging sign that such payments would one day become the norm. More than a decade later, the fact of the matter is — it didn’t happen.

Many vendors, including Tesla, Microsoft, Steam and Dell, all tried to accept Bitcoin at some point, before giving up for various reasons: low demand, instability of the exchange rates, or even concerns about the ecological impact (more on that later). As far as currencies go, Bitcoin has failed. I expect that many cryptocurrency proponents would dispute that statement, but let’s face the facts:

- It’s almost impossible to find stores that accept Bitcoin.

- Validation delays for transactions are prohibitive. If you were to go to a store intending to pay with Bitcoin, you’d have to wait at least ten minutes before you could leave.

- Bitcoin payments incur transaction fees (fees given to the participants of the network as payment for confirming transactions). They are currently relatively low, in the order of $1 per transaction, but reached almost $60 during the 2017 boom.

Long story short, even if you were to find… a bakery willing to give you a baguette in exchange for Bitcoin, you’d both clog the line for a long time and end up paying twice as much for your bread as its retail price. There are only a limited number of use-cases where none of these issues apply, and they can pretty much be reduced to buying drugs and paying ransoms — both of which have debatable social utility. Still, Bitcoin being a dreadful payment system doesn’t mean it hasn’t accomplished anything: people are currently willing to pay over $23,000 for 1BTC… So it must have some use, right?

Polling cryptocurrency enthusiasts you may know, you’ll soon discover that almost none of them purchased Bitcoin to spend it (at least, not for the purposes they’d be willing to admit), but instead with every intent to resell it at a profit. The number one reason why people buy Bitcoin is speculation: while the project failed as a currency, it greatly exceeded expectations as a gambling system. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve nothing against gambling; it’s just that confusing it with anything else usually leads to financial ruin. Still, if we established at the very beginning that your aim in all this is to get filthy rich — no problem here: we’re still on the right track!

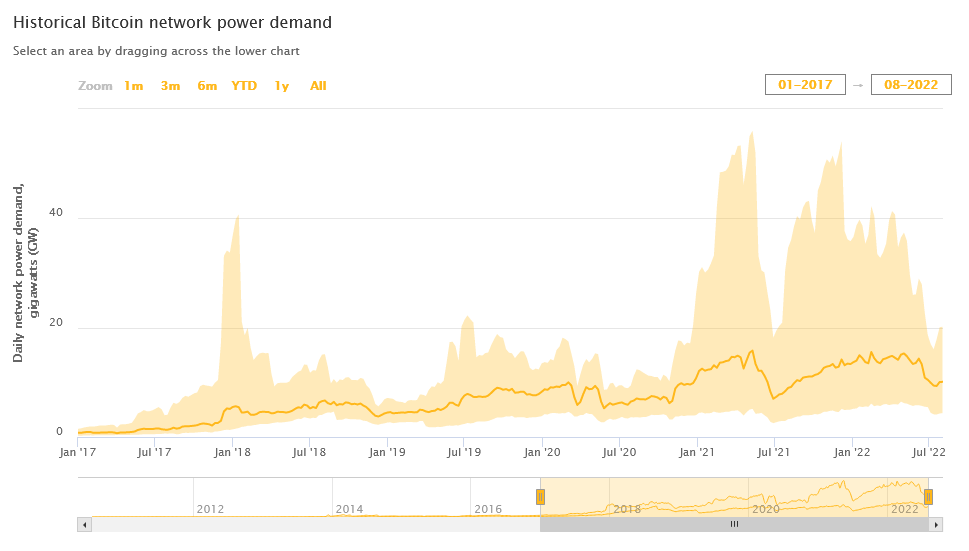

If there’s one thing the cryptocurrency world loves, it’s a line going upwards.

Source: Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index

Criticism of Bitcoin doesn’t end there. One of the major arguments against it is how dreadfully inefficient the network really is. It can only handle three to seven transactions per second (TPS), as opposed to actual payment processors such as Visa and MasterCard (1700 and 5000 TPS, respectively, with a maximum capacity way beyond that). Ethereum, another major blockchain, reports 15-25 TPS on average — slightly better but still light-years away from any form of scalability. Those numbers could be overlooked if the cost for reaching those measly 3-7 TPS wasn’t so unbelievably high. Each transaction requires a power consumption of over 2000 kWh, totaling an estimated 89 terawatt-hours (TWh) for 2022 (live statistics can be found here). Compare that with MasterCard’s 0.000109 TWh consumed in all of 2019, while keeping in mind that they could do a thousand times more with that energy. Now compare that with the 2021 consumption of France (441 TWh) or Germany (503 TWh), and try not to think too much about the fact that Europe is in the middle of a major energy crisis [1]Counter-arguments from blockchain enthusiasts related to these problems are studied in the next section..

The cause of this absurd energy consumption is a mechanism called “proof-of-work”. I mentioned earlier how blockchains need to provide a certain number of guarantees — one of which is the fact that malicious actors cannot inject false information into the ledger. To prevent this from happening, each block added to the chain needs to be validated by the network. This process involves having participants of the network compete to solve a complex problem [2]Whoever finds the solution to the problem first receives a reward (currently, 6.25 BTC). This process is called “mining” and this is how new currency appears in the system. If not for this reward mechanism, nobody would have an incentive to help validate transactions and the whole system would crumble.; the underlying idea being that no attacker would ever be able to waste enough computing power (that is, energy) to outperform the rest of the participants. Here’s an example of the kind of hardware you need for a decent shot at a solution:

A 2500 GPU mining farm [3]Graphics cards are very efficient at the type of operations mining involves, and are the primary hardware components used by miners. Their demand incidentally drove a worldwide shortage we’re still struggling with.. Source

A short masterclass in wishful thinking

Proponents of cryptocurrencies are quick to point out that many (if not all) of the problems outlined in this first section are related to poor design choices made during Bitcoin’s inception, and that blockchains in 2022 are not what they were in 2010. You’ll have no doubt noticed how I keep referring to “blockchains” — plural. That’s because many exist today, each implemented with different properties in mind. In light of this, here are the two main counter-arguments routinely offered:

- There are alternatives to wasteful proof-of-work algorithms, such as proof-of-stake [4]Proof-of-stake algorithms will be discussed in more detail in another section of this article, as they trade energy consumption issues for worsened governance problems. ones;

- Research is ongoing to improve the number of transactions-per-second handled by blockchains, possibly via so-called “Layer 2” protocols like Lightning [5]Lightning is a protocol built on top of Bitcoin, relying on smart contracts to open payment channels between users (at the cost of immobilizing some capital). A system loosely comparable to balance sheets allows users to transfer money among themselves until they decide to cash out, at which point the resulting transaction gets committed to the blockchain. Ironically, the solution offered to blockchain inefficiency by these L2 protocols usually involves taking transactions outside of the blockchain, or worse: giving up on decentralization..

And those proponents seem to be right: blockchains don’t have to be as dreadful at what they do as Bitcoin, and the whole technology can still be argued to be in its infancy. There’s no doubt in my mind that they can be improved dramatically. Unfortunately… none of this matters. The history of sciences teaches us that the diffusion of technologies, no matter how groundbreaking they are, takes dozens of years at best.

Case in point: no matter what cool new blockchains are designed this year, Bitcoin and Ethereum are still the dominant ones, and it’s unlikely this will change in the foreseeable future. Even though the major players might integrate new contributions to the field (such as Ethereum ditching proof-of-work algorithms), this will only happen on a case-by-case basis, over long periods of time, and within a limited scope. In other words, barring a major ecosystem overhaul of cataclysmic proportions, the current blockchains and all their problems (including some I’m not getting into here [6]Most of the remaining discussion on cryptocurrency challenges revolves around the privacy guarantees they offer (not that many in the case of Bitcoin). My feeling is that such considerations don’t matter too much in the grand scheme of things now that we’ve established that cryptocurrencies can’t be used to purchase anything anyway.) will persist in a more or less identical fashion.

The broken libertarian promise

The final nail in the coffin, however, comes from a very unexpected angle, and with a blunt force that reduces everything discussed so far to meaningless dust. Decentralization, as I insisted heavily in my introduction to blockchains, is cryptocurrency’s raison d’être. Its most adamant defenders may go as far as saying that all the costs and impracticalities laid out above are the price they’re willing to pay for peer-to-peer payments that genuinely eschew the need for trusted third-parties. Watch the four-minute Declaration of Bitcoin’s Independence [7]The folks in this video may not represent the official position of Bitcoin’s current maintainers (if they even have one), but are representative of views shared by many in the cryptocurrency community. (here’s the transcript for those who prefer reading over viewing) and see if you can spot the anti-establishment language.

Here’s my point: if cryptocurrencies don’t offer proper decentralization — a genuine alternative to state-monitored, bank-controlled payment systems — they might as well not exist at all. What would centralized cryptocurrencies be then, if not a much worse way of providing a service already handled by Visa and MasterCard?

Brace yourself for an uncomfortable truth: blockchains aren’t really decentralized after all. And this is true on many levels. Using Bitcoin as an example again, you’ll remember that due to proof-of-work, users need to be able to provide tremendous amounts of computing power to participate in the network. Do you own a GPU farm like the one shown in the picture above? If not, it’s highly unlikely you’ll ever be able to validate a transaction. To make things worse, big players, who are rewarded for being the first to validate a transaction, increase their chances by pooling their resources together, leading to even further concentration of the processing power of Bitcoin.

Hashrate distribution in the Bitcoin network. Source

The diagram above shows that at the time of this writing, more than half of transactions on the Bitcoin network are handled by just five entities. Ethereum seems to be in a similar predicament. If one of these entities were to reach 51% of the share, it would be a disaster because — remember — blockchains are in large part consensus protocols. There’s no point in consensus when someone has the majority: they can just decide whatever they want.

Admittedly, we don’t appear to be anywhere near that point, so Bitcoin and Ethereum are still technically decentralized. But we’re also very far from the original peer-to-peer ideal: there’s no way for you, as a newcomer, to meaningfully participate in the network. And where any decisions need to be taken concerning the future of these blockchains, it’s obvious that these entities’ voices will matter more than yours.

Proof-of-stake algorithms, alluded to previously, propose to replace the very wasteful proof-of-work schemes by basing validation not on the raw energy you can leverage, but on the amount of currency you can offer as collateral. While there’s no question that the planet will be better off, it’s also very obvious that such algorithms place power in the hands of a limited number of wealthy individuals you cannot ever hope to join. To no-one’s surprise, Silicon Valley’s self-proclaimed libertarian tendencies have given birth to a variation of late-stage capitalism (where they’re at the top).

A good illustration of this issue is Ethereum’s planned switch to a proof-of-stake algorithm later this year. It’s not a decision I’m criticizing, considering how much energy it will end up saving. However, one cannot help but notice that a crypto-aristocracy changes the rules of the game that apply to everyone — in a way that will arguably consolidate their power over the ecosystem as a whole [8]More information about Ethereum’s decision process can be found here. It’s stated there that “Ethereum governance happens off-chain with a wide variety of stakeholders involved in the process.”.

But wait… There’s more! Trail of Bits also has an excellent research paper titled Unintended centralities in distributed ledger, detailing other technical challenges to decentralization in blockchains [9]You may also be interested in this 2019 article containing mathematical proof of the “impossibility of full decentralization in permissionless blockchains“.:

- The number of entities needed to disrupt the network is a lot lower than you’d expect;

- Blockchain developers concentrate a disproportionate amount of power, which can only be contested through highly disruptive forks.

Overall, blockchains are (strictly speaking) decentralized in the sense that they’re not controlled by a single entity, yet they’re very much centralized in practice due to the fact that a few entities hold most of the power.

Basically — backdoor banking

So we’ve established that blockchains aren’t really decentralized after all. But what about the cryptocurrency industry? Is it truly composed of die-hard activists aiming to free humanity from the thrall of corrupt states, as advertised on the label?

A quick survey of the biggest names in the cryptocurrency field says “hell no”. Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Jack Dorsey and the Winklevoss brothers, to name a few, are all purported to have invested massively into cryptocurrencies. Do tech billionaires harbor a secret agenda to give power back to the people? That’s unlikely: I doubt that the richest 1% people in the world have much interest in toppling the overall capitalist framework from which they are benefiting so much.

Let’s take a look at the broader picture. Say, after all this, you still want to buy Bitcoin. How do you get some? Odds are, you’ll look for an online exchange that will turn your hard-earned dollars into the cryptocurrency of your choice [10]Yes, there are ways to set up a meeting with private sellers and perform the exchange offline, but we all know you’re not going to do that. In any case, this only represents a marginal fraction of all transactions.. These platforms act as the gatekeepers to the cryptocurrency world. They’ll ask for a copy of your passport, verify your identity to comply with state regulations, and you’ll then be able to deposit money via wire transfer or credit card. You can then use your balance on the platform to purchase cryptocurrency — for a fee of course.

There are many platforms you can choose from, but looking at their partners paints a worrying picture:

- Bitstamp is in bed with the French bank Crédit Agricole;

- FTX, which famously advertised during the Super Bowl, appears to be in talks with Goldman Sachs;

- Coinbase received a $10.5M investment from the Bank of Tokyo.

I could go on. But why would banks actively fund a technology whose ideological bedrock is to make them obsolete? The answer is, obviously, that it isn’t the case. Banks have recognized cryptocurrencies for the speculative vehicle that they are and have put themselves in a position to both join the party and act as intermediaries when you do too — because… well, there’s money to be made.

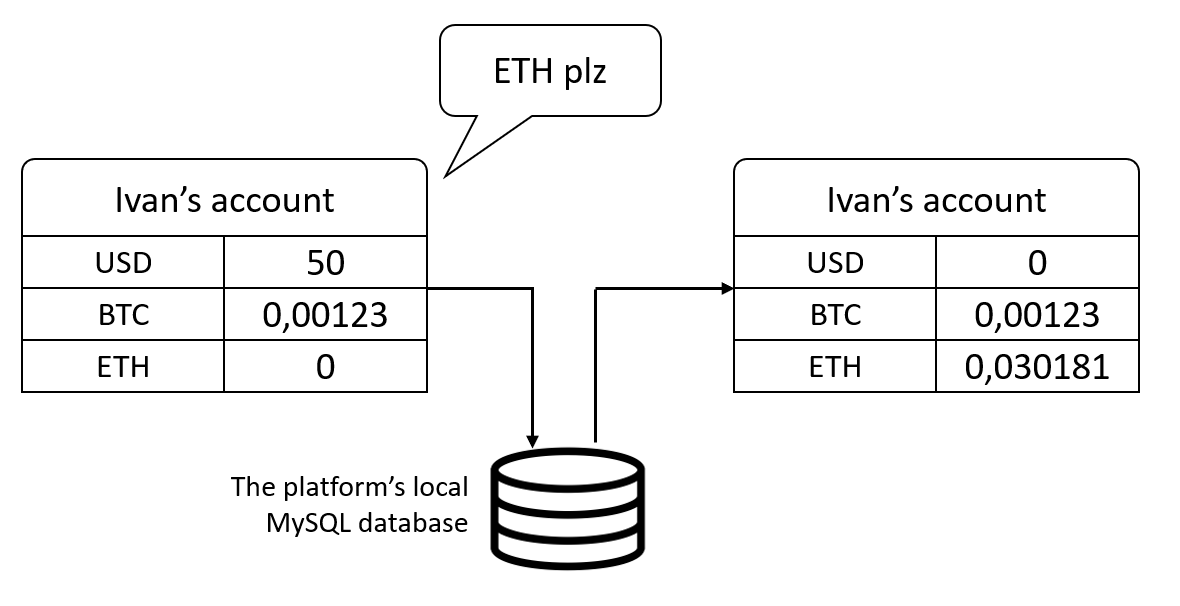

The icing on the cake is the way that such exchanges work under the hood. As it turns out, when you purchase cryptocurrencies, platforms simply update your balance in their local database — because, again, using the blockchain would be too expensive and slow! Many cryptocurrency traders have never, in fact, sent out a single transaction to the blockchain, because all they do is convert back and forth between currencies to profit from fluctuating exchange rates… and these operations occur locally.

And this is where we come full-circle: access to the cryptocurrency world can only be achieved through a handful of corporations, which essentially keep track of how much (crypto-)money you own until you decide to withdraw it. If this isn’t the exact definition of the banking industry we wanted to escape in the first place (and rebuilt with their funding and guidance, no less), I don’t know what is.

Conclusion

This certainly was a long ride — yet, incredibly, things only go downhill from here. While the broader subject I wanted to address was NFTs, it’s impossible to understand their grave misgivings without having a decent grasp of the dumpster-fire of a foundation they’re built upon. In the interest of clarity, let me sum up the key points established up to now:

- Blockchains, as a technology, are consensus-building algorithms stapled onto distributed databases. They’re very inefficient at what they do, which they compensate (allegedly) by being decentralized.

- Cryptocurrencies were initially designed as an alternative to real-world currencies — a goal they have miserably failed to reach. They immediately degenerated into highly volatile speculative assets and have served zero practical purpose ever since. Blockchains remain a solution in search of a problem.

- The core promise of decentralization hasn’t even been fulfilled, which deals a fatal blow to the whole endeavor. Centralized cryptocurrencies are just digital banking and we already had that, only better implemented in every imaginable aspect. But we got there under the guise of building the conceptual opposite, which, in retrospect, was worth it for the sheer irony.

In the next episode: Ethereum’s smart contracts, non-fungible tokens, and the subtle art of making incredibly unique jpeg images on an industrial scale. Stay tuned!…

cryptocurrencies

cryptocurrencies