Our lives will be smooth once PCs are embedded into our brains. Text messages will be replaced by ‘mentalgrams,’ whispered to us subtly by our inner voice. Has a bright idea just popped into your head? Share it with your friends via a brainwave! Recall your wife’s groceries list for just $2.99.

Then immature bio-discreet interfaces will stream data at the rate of terabytes per minute to the computers (which will be, essentially, display-less smartphones), leaving the function of searching the entirety of the background noise for sense and need for more powerful processors of the future.

In simple words, the brand new iPhone 164 will know everything about you. Google, which will have lived through 34 rebranding campaigns and 8 restructuring efforts, will store and process this data in its data centers which will occupy over 2% of the Earth’s surface. Only then, when this technology breakthrough is a bit more mature, will they think of securing those immense volumes of data.

Unfortunately before this data is secured, it will probably hit the black market. Only then we would finally think of what data we collect and store and how.

How direct neural interfaces work and how it refers to data security http://t.co/UZ9H7CmZQX

— Eugene Kaspersky (@e_kaspersky) May 1, 2015

This is bound to happen later. Speaking of today, I wonder whether anyone cares about how much user background a collection of gyroscope data would reveal. Security research frequently lags behind the commercial technology, and tech designers would rarely give a second thought about security when creating their gizmos.

In today’s digest of the last week’s key news will cover software and devices of today, which have been available to millions of users for some time. Once again, the rules of the road: every week Threatpost’s team handpicks three important news stories, which I offer commentary. All previous editions can be found here.

A Trojan steals data from jailbroken iPhones

News. Palo Alto Networks research. Short explanation of who should worry.

Not all reports on leaks or bugs are easily explained in human terms, yet this one is. In China, a rogue iOS app was found; it sneaks into communications between a smartphone and Apple’s servers and steals iTunes passwords. The malware got busted because it attracted too much attention: many users started to report theft from their iTunes accounts (for the record, the bank card is tied by a dead knot to an Apple account and the only thing you need in order to pay for Angry Birds is a password).

KeyRaider #Malware Steals Certs, Keys & Account Data From Jailbroken #iPhones: http://t.co/RKlDhcJc1m via @threatpost pic.twitter.com/IZ90PMfRXx

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) August 31, 2015

Cool, right? Wrong! The attack concerned only jailbroken users. Independent researchers from China who attributed themselves to WeipTech have accidently broken into the cuplrits’ C&C server and found over 225,000 user credentials (amazing how many people are into jailbreaking), including username, password and the device’s GUID.

The malicious app is side-loaded from Cydia, an alternative iOS app store. Then it embeds itself into communications between the device and Apple servers, following the good old Man in the Middle method and redirects the hijacked data to its own server. And now – the icing on the cake: the malware uses a static encryption key, ‘mischa07’ (FYI: in Russian ‘Misha’ stands both for pet form of name Michael and for ‘bear‘).

Mischa07 steals iOS users’ passwordsIt remains unclear whether that ‘Mischa’ managed to earn a fortune on the KeyRaider attack. Still, the morale here is that a jailbroken iPhone is even more susceptible to attacks than an Android device. Once the robust iOS protection is compromised, it turns out that no other protection means are in place and anyone can do, basically, anything.

It’s a common flaw for all robust systems: on the outside, powerful firewalls and physical means of protection are deployed at the perimeter, the system itself is disconnected – all in all, the system is a fortress. But on the inside, it represents a mediocre Pentium 4 PC running Windows XP, which was last patched back in 2003. But, in this case, what if someone has infiltrated the perimeter?

The question pops up with regard to iOS: what could happen if a simple and operational root exploit emerged? Does Apple have a Plan B? Might this prove Android has an advantage, after all, since it presupposes the chance to be hacked and the developers act respectively?

Google, Mozilla and Microsoft (even earlier) will bid farewell to RC4 in 2016

News.

Last week’s installment of Security Week (the one where we discussed the man-on-the-side DDoS attack on GitHub) we concluded that using HTTPS is blessing both for a user and a web service owner. That remains so, besides the fact that not all HTTPS deployment are good for your health – moreover, some of them, which employ ancient encryption methods, are even hazardous.

To cite a couple of examples, let me remind you of the role of SSLv3 in the POODLE attack and, basically, everything, which employs the RC4 encryption. If SSLv3 has just turned 18 and can enjoy a lot of adult things now, RC4 dates back to as long ago as 1980s. With regard to the web, it’s hard to know for sure that the use of RC4 results in a compromised connection, per se. Earlier Internet Engineering Task Force admitted that theoretically attacks on RC4 are likely to be soon performed in the wild.

By the way, here’s the result of a recent research: a downgrade from any robust encryption to RC4 allows one to decrypt cookies (which means to hijack the session) in just 52 hours. To succeed, one needs to hijack some cookies, bearing in mind the likely outcome, and then bruteforce the website, thus enjoying higher probability of success. Feasible? Yes, considering several variables. Was it used itw? No one knows. In Snowden’s files there were allegations that intelligence services are able to crack RC4.

Well, the news is positive: a potentially vulnerable encryption algorithm has not even been cracked (at least not on the global scale) before getting blocked for good. Even now, the case is quite rare: for Chrome, it constituted only 0.13% of all connections – however, in absolute numbers, it’s helluva lot. The RC4 burial is officially celebrated from January 26 (for Firefox 44) to the end of February (for Chrome).

Microsoft also plans to ban RC4 early next year (for Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge), due to impossibility to tell apart a mistakenly induced TLS 1.0 fallback of a RC4 website from a man-in-the-middle attack.

I cannot help but spoil this optimism with a bit of skepticism. Such upgrades would usually impact either laggy, godforsaken websites or proven critical web services which are not that easily changed. It’s highly probable that early next year we will witness vivid discussions about someone being unable to log into a sophisticated web banking tool after the browser update. We’ll live, we’ll see.

Vulnerabilities in Belkin N600 routers

I genuinely love news about router vulnerabilities. Unlike PCs, smartphones and other devices, routers are likely to remain forgotten in dusty corners for years, especially if the router functions uninterruptedly. So, no one would even bother to know what happens inside that little black box, even if you deployed brand new OpenWRT-based custom firmware, especially if you are not a power user and your router was set up for you by your network provider.

.@CERTCC Warns of Slew of Bugs in @Belkin N600 Routers – http://t.co/70EfVwxIS0

— Threatpost (@threatpost) August 31, 2015

With that in mind, a router has a key to all of your data: whoever would be able to get into your local file sharing platform, hijack your traffic, swap your web banking page for a phish page, or embed undesired adverts into your Google search results. It’s possible, once someone breached into your router through a single vulnerability or, which is even more likely, through a vulnerable default configuration.

I would have liked to affirm that I update the router firmware at once as soon as the new version is out, but that’s not true. My best shot is in once every six months – solely thanks to built-in browser notifications. I used to update my previous router more frequently – only to battle constant glitches. For some time, my own router was susceptible to a remote access vulnerability.

Root Command Execution Flaw Haunts ASUS Routers – http://t.co/0oYb1F8T12

— Threatpost (@threatpost) January 8, 2015

Five solid security bugs were found in Belkin routers, including:

- Guessable transaction IDs when sending requests to the DNS server, which, in theory, would allow to replace the server when, for instance, calling server for the firmware update. Not a big deal, though.

- HTTP used by default for critical operations – like requests for firmware updates. Spooky.

- The web interface not protected by password by default. With this bug, anything can be replaced, however, provided the attacker is already inside the local network. Level of spookiness – medium.

- Password-enabled authentication bypass when accessing the web interface. The thing is that the browser notifies the router whether the latter is logged in, and not vice versa. Just replace a couple of parameters in the data fed to the router, and no password is required. Level of spookiness – 76%.

- CSRF. Once a user is lured into clicking on a specially crafted link, an attacked is able to tamper with the router’s settings remotely. Spooky as hell.

Alright, they found a series of holes in a not-so-popular-here router, big deal. The problem is that not many folks are into hunting bugs in routers, so the fact the vulns were found in Belkin does not mean other vendors’ devices are secure. Maybe their time will come. This selection of news proves the state of things is very, very poor.

Default credentials on home routers lead to massive DDoS-for-hire botnet – http://t.co/2SbvLcwcvu pic.twitter.com/20O0GWwVOt

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) May 13, 2015

So, what’s the takeaway? One has to protect their local network hard as they can, even with the available toolset: protect the web interface by password, not use WiFi through WEP, as well as disable WPS and other unused features like FTP server and telnet/SSH (especially external) access.

What else happened?

USA plans to impose sanctions on China due to their massive cyberespionage campaigns. This was one of the most popular news of the week, yet it has its peculiarities: it will have no impact whatsoever on cybersecurity or threat landscape, in any case – just politics and nothing more.

Routers are not the most vulnerable devices ever. Baby monitors and other ‘user-friendly’ devices are even worse. Absence of encryption and authorization and other bugs are in the plain sight.

Who is to blame for “hacked” private cameras? https://t.co/WItQAZKAbU #security #webcams pic.twitter.com/k7LcRXH6vX

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) November 21, 2014

A new method of hijacking group pages on Facebook was found; the blame is on the Pages Manager app. The vulnerability has been patched, and the researched received a bug bounty award.

Oldies

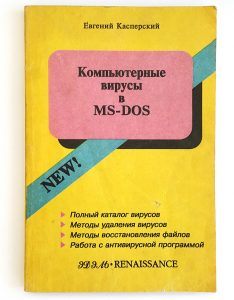

The Andryushka family

Those are very dangerous resident ‘ghost’ viruses. They plague COM and EXE files (except COMMAND.COM), when launching the infected file (in catalogue search) and from launching its TSR copies (when opening, executing, renaming, etc.). Andryushka-3536 converts EXE files into COM (here refer to the VASCINA virus). The virus is deployed into the middle of the file, with the part of the compromised file, where the virus writes itself into, encrypted and written to the end of the infected file.

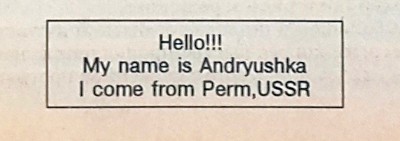

They deploy counter registers in Boot sectors on hard drives and, depending on the value of the counter register, are able to corrupt several sectors on the C:// drive. During the process, they play a melody and display the text on the monitor:

They also include the text: insufficient memory. They employ a sophisticated method of working with ISRs: they preserve a part of int 25h handles in their body, and overwrite their own code (int 21h call) in the available space. When int 25h is called, they restore the int 25h handler.

Quoted from “Computer viruses in MS-DOS” by Eugene Kaspersky, 1992. Page 23.

Disclaimer: this column reflects only the personal opinion of the author. It may coincide with Kaspersky Lab position, or it may not. Depends on luck.

apple

apple

Tips

Tips